|

I. CPD Needs Assessment

Moving Towards Mastery—A Needs Assessment of Online CPD Provision During the Pandemic

III. Building Capacity and Effective Teams

Beyond Grand! Grafting a Structured Reflective Tool to Hospital Rounds

Holding Braver Conversations: Interpersonal Conflict Simulations

How to Collaborate Successfully in Online Educational Programs for Latin America

Monitoring and Evaluating AI: Challenges and Practical Implications

Practice Assessment Tools for Medical Specialists—A Bridge to Quality Improvement

Developing a Patient Safety Culture Training Curriculum for Healthcare Professionals

Preparing Physicians to Lead Organizational Change

IV. Innovation and Adapting in Changing Times

A Call to Action: Committing to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in CPD

CPD Diversity Audit: Tracking and Reflecting on CPD Decisions for Advancing Justice

Regularly Scheduled Series (RSS’s)—Reimagined

Reimaging Bias: Making Strange with Disclosure

Success of Virtual Platform for an Established “Train the Trainer” Course

Perspectives and Innovation in Educational Design from the GAME Futurist Forums

Educational Needs for Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) for COVID 19 Pandemic in a Low Middle Income Country

Authors: Savithiri Ratnapalan, PhD, MBBS, Niranjala Perara, MD, MSc, Vitoria Haldane, PhD (C), MPH, Sudath Samraweera, MD, PhD, Xiaolin Wei, PhD

Institution: University of Toronto, Hospital for Sick Children

Background/purpose/inquiry question

Prior to developing educational materials on infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for Covid-19 pandemic management, we conducted this study to identify learning needs of health care workers (HCW) in Sri Lanka.

Theoretical framework(s)

Semi-structured interviews conducted using a grounded theory methodology

Methods

Sixteen participants including nine physicians (including three policy- makers responsible for COVID-19 pandemic management ), three nurses, two public health midwives and two support workers ( cleaning and transport staff) were interviewed.

Results/findings

Interview findings are described under three themes: HCWs workload; pandemic management guidelines and education provided; and guidelines and education desired. The pandemic increased staff workload for both in hospital and community HCWs; HCWs were provided with some form of IPC training but there were lapses in adherence; staff were interested in having easy to use desk guides, training videos and multimodal training.

Discussion

Our results highlight that a tailored approach to IPC education based on identified overall and key specific needs (such as training support staff) provides crucial information to improve HCW capacities in LMICs in response to either COVID-19 or future public health emergencies.

Limitation

The training needs identified in this study are from one LMIC country and in some regards are likely specific to the context in Sri Lanka. As such, the authors do not claim any generalizability.

Impact/relevance to the advancement of the field of CME/CPD

Our results show that many support staff have expanded scopes of practice and provide a significant amount services involving patient or patient environmental contact and need to be continuously educated along with other frontline staff on IPC practices.

Moving Towards Mastery—A Needs Assessment of Online CPD Provision During the Pandemic

Authors: Heather MacNeill, MD, MScCH (HPTE), Morag Paton MEd, Suzan Schneeweiss, MD, MEd, David Wiljer, PhD

Institution: University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

COVID19 moved online CPD delivery from "nice to do" to something CPD providers "had to do", requiring additional skills and competencies. This study describes CPD providers’ comfort, resources, perceived advantages/disadvantages, and consensus on issues around privacy and copyright, in technology-enhanced CPD.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

A 26-item online survey was deployed through Qualtrics and piloted. The survey gathered information from CPD providers at the University of Toronto (UofT) and SACME about moving from face-to-face CPD delivery to virtual. Descriptive statistics were analyzed using SPSS. This work is informed by Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy, the technology acceptance model, and the community of inquiry framework. Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion The survey had a 15.5% response rate. 81% felt confident to provide online CPD, but under half reported access to IT, financial, or faculty development supports. The most reported advantage to online CPD was reaching a new demographic, with virtual meeting fatigue the most reported disadvantage. There was interest in using collaboration tools, virtual patients, and augmented/virtual reality in future CPD delivery. There was inconsistent consensus on privacy and copyright issues.

Identified themes included 1) Social and learning norms in the online environment are evolving and contextual, 2) CPD providers recognize the importance of promoting active learning but need further training and resources to learn how to do this well online, 3) Accessible and safe learning environments are components of successful interactive online CPD programs and 4) Adequate preparation by learners, presenters, and providers is important for effective online CPD.

The necessity of COVID-19 helped develop a comfort level in providing online CPD, but further support is needed to develop best practices.

The response rate may limit generalization of the results, however the consistency in responses between UofT and SACME participants is reassuring.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

This research has implications for our collective ability to move towards best practices in CPD technology enhanced delivery. We need to pay attention to emerging issues such as evolving norms, interactivity, accessibility, and preparation while making sure we offer sufficient resources, including funding and faculty development to build best practices for the future.

Adoption of Telehealth by Clinical Teachers, Supervisors and Clinical Practitioners at McGill University and Teaching Hospitals: A Needs Assessment

Authors: Francesca Luconi, PhD, Beatrice Lauzon, Lalla L, Mercer G, Levin L, Arsenault M, Elizov M, Jarvis C.

Institution: McGill University

Problem statement

Telehealth predates the Covid-19 pandemic1,2 and evidence suggests that it can expand critical care, speed emergency care decisions, replace face-to-face care and reduce exposure to infections3.

The WHO defines telehealth as: “[t]he delivery of healthcare services (…) by all healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research, and evaluation, and for the continuing education of healthcare providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities”4

Although the use of telehealth has increased worldwide in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, little is known about the needs of academic leaders and clinical practitioners in adopting telehealth in Quebec, Canada.

Our aim was to investigate perceived and unperceived needs of practicing physicians in Quebec and to identify barriers and enablers to using telehealth (TH).

Research Method

A needs assessment (NA) is a systematic process of collecting and analyzing data on the target audience’s educational needs5 and a comprehensive needs assessment is crucial to planning and developing relevant continuing professional development6. We collected data via two online surveys exploring physicians’ perceived needs, which can be defined as what learners think they want to learn6. One survey (S1) targeted academic leaders (i.e., clinical chairs and division directors in departments of medicine) while the other surveyed practicing physicians (in their roles of teacher at undergraduate or post-graduate levels, supervisor of trainees and/or clinical practitioner) affiliated with McGill University and its teaching hospitals (S2).

Unperceived needs can be defined as “I do not know what I do not know”6. These were investigated via a report on medico-legal cases and advice calls involving telehealth (from the Canadian Medical Protective Association or CMPA) as well as questions about participants’ reported challenging cases in diagnosing and treating patients using TH (from S2).

Descriptive statistics, deductive thematic analysis and triangulation of sources were conducted on these data.

Outcomes and Discussion

S1 (conducted in 2020) included a convenience sample of 20 clinical chairs (60%) and division directors in departments of medicine (40%) representing 12 medical specialties. Most respondents anticipated a high uptake of TH for teaching and supervision of trainees.

S2 (conducted in 2021) included 250 physicians of which 53% were family physicians and 45% other specialists. Their demographic profile covered a range from more experienced to less experienced professionals (55.3% ≥16 years 20.4% ≤5 years of experience as clinicians).

Beginning in March 2020, adoption of TH was high across teachers, supervisors and clinicians. The most frequently reported role was clinical practitioner (64.8%) where use of telehealth ‘often’ or ‘very often’ increased from 10.1% to 88.3%.

Increased use of telehealth was also reported by the CMPA which received 970 advice calls related to telemedicine between January 1st, 2019 and May 2020, with 70% of the calls were made in the period of March – May 2020. 69% (of a subsample n=478 calls where TH was the main reason for the call) focused on the adoption of TH to continue duty of care for existing patients during the pandemic and 64% reported using the telephone for consultations.

Before the pandemic (2015-2019) the CMPA reported on 45 medico-legal cases involving the use of TH, reporting on influencing factors at the individual, team and systemic levels. Delayed diagnosis when using TH was the most reported challenging case by our participants in S2. Their needs during the pandemic coincided with unperceived needs reported by the CMPA prior to March 2020. One of the most frequently reported factors at the provider level in both sources was provider deficiencies with regards to selecting appropriate technology for patient care. (Inadequate monitoring and follow-up were also reported in S2, while procedural violations were reported as a factor in the CMPA analyses.) At the team level major factors were communication breakdown (with patients and/or other physicians, identified by S2 and CMPA), as well as deficient record keeping (CMPA only). While few system level factors were reported, both sources reported that lack of/inadequate office policies, procedures or practices as a factor at this level.

Triangulation of sources indicated some consistency with regards to major barriers to and enablers of the adoption of TH. At the individual/provider level, perception of impersonal care/interaction and privacy/security concerns were barriers reported across more than one source. Organizational barriers reported across 2 or more sources included outdated hardware, restricted remote access to medical records and electronic charting, as well as infrastructure. Top enablers across ≥2 sources included TH’s safety as well as its ‘timeliness’. Thematic analyses suggest that in clinical practice TH was usually adopted when physical exam was not required, for follow-ups and for care of specific types of patients; limited patient access to TH was due to lack of or limited digital health literacy. These results suggest the need for implementation of strategies to address and mitigate challenges for vulnerable patients.7,8

In conclusion, physicians’ use of TH for patient care has greatly increased in response to Covid-19 yet important barriers remain. Identified gaps and facilitating factors might trigger sustainable change at multiple levels if identified needs can be met. Limitations of our study include the timing of data collection, which varied across sources. Differing timing could therefore have affected triangulation of results. In addition, medico-legal cases are not representative of all physicians’ use of TH and generalizability of findings may be limited due to the use of a convenience sample.

Learning AI, Making it Real: A Qualitative Study of the Needs of Medical Educators for Artificial Intelligence Program Development

Authors: David Wiljer, PhD, Mohammad Salhia, Med,Sarmini Balakumar, BSc, Tharshini Jeyakumar, MHI, Sarah Younus, MPH, Rebecca Charow, MSC, Melody Zhang, MA, Elham Dolatabadi, PhD, Azra Dhalla, MBA, Caitlin Gillan, PhD, Dalia Al-Mouaswas, BSC, Jacqueline Waldorf, EMBA, Jane Mattson, MLT, Megan Clare, MA, Walter Tavares, PhD, Ethan Jackson, PhD

Institution: University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

The National Academy of Medicine highlight the need for developing, deploying, and evaluating AI educational programs to support the safe, effective and sustainable use of AI in clinical practices. This study informs the third phase of a multi-stepped approach to accelerating the appropriate adoption of AI in health care, and is informed by the Knowledge-to-Action framework. Specifically, it aimed to understand the current landscape of AI education for health care professionals and recommendations for future education program development.

Approach(es)/Research Method/Educational Design

A qualitative approach was taken to explore the needs of educators and learners of AI education programs targeted at clinicians, leaders and scientists in healthcare. Virtual semi-structured interviews informed by the Kirkpatrick Barr (for learners) and RE-AIM (for educators) frameworks were conducted. These interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

A total of 17 participants were recruited for the study: 10 educators and 7 learners. Three major themes emerged about AI education approaches, which were valued by both learners and educators: (1) practical experiences to support the transfer of learning, (2) multidisciplinary approaches to curriculum development and course delivery, and (3) balancing learner needs and promoting engagement through a learner-centered pedagogy when developing AI education programs. The first theme highlighted the importance of hands-on activities such as workplace learning, debates, and group-based learning and access to appropriate resources (i.e., health data). The second theme focused on co-designing the curricula collaboratively with experts from various disciplines as well as providing opportunities to engage in multidisciplinary learning to replicate real-world scenarios and fit with industry demands. The last theme stressed the importance of selecting an appropriate mode of delivery and continuously evaluating the program and learners.

This study was presented at SACME as an oral presentation, under the category of CPD needs assessment. The presentation was given to approximately 200 attendees. The study received positive feedback from the audience, with several individuals raising thoughtful questions and comments that energized the conversation. For instance, one question revolved around the topic of patient involvement in AI adoption and implementation. There was curiosity on whether research on AI has gone beyond clinicians and researchers to include patient perspectives, such as patient acceptability towards AI, eHealth or digital eHealth initiatives. Although patients and patient advocates have been included in various aspects of our study project, including: (1) a steering committee where patients were engaged during the planning and development of our project, (2) a needs assessment interview with patients to understand their perspectives and attitude towards AI, as well as (3) patient participation in our AI certificate program, many issues must still be addressed. For instance, a gap in the literature still exists on patient consent with AI; further research should examine this in relation to care delivery.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

The findings from this study can be used to advance CME/CPE through the development of practical AI education programs in healthcare. In partnership with The Michener Institute of Education and the Vector Institute, we have developed an evidence-based education program, “AI for Clinical Champions” that will empower a Canadian workforce with the appropriate skills, knowledge, and capabilities to adapt and implement AI into clinical practice and healthcare organizations. Future directions include the continuous evaluation and improvement of education programs to ensure the effectiveness and relevance for learners. Furthermore, to encourage discourse within the research, clinical, and general community, engagement activities such as national or international symposiums will be held to engage a greater audience in conversations about AI in health care.

Impact of Culture on Combatting Burnout and Stress in the Field of Laboratory Medicine

Authors: Lotte Mulder, PhD, Edna Garcia, MPH, Joseph S. Sirintrapun, MD, Iman Kundu, MPH

Institution: American Society for Clinical Pathology

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

Little research has been conducted concerning organizational culture issues impacting the field of pathology and lab medicine, especially when it comes to well-being and burnout. When the COVID-19 pandemic happened, the laboratory field was profoundly impacted. This prompted us to identify the connection between burnout, the pandemic, DEI, and organizational culture to further support our workforce.

The overall purpose of this study is to understand the unique pressures of COVID-19 in pathology and laboratory medicine, develop strategies to mitigate burnout and toxic organizational cultures, and advocate for and create resources to improve DEI and wellness within the laboratory.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

To capture data about culture, burnout, DEI, and wellness from medical laboratory professionals during the pandemic, the study utilized a cross-sectional survey design. Because the pandemic continues to affect the field in so many areas, this study has become a longitudinal study. The theoretical framework used in this study is based on the interrelationship between burnout, DEI, and organization culture and its components, such as structures, systems, and behaviors.

This study was divided into two phases. Phase 1 was launched in August 2021, with an online survey that was deployed for one week. There were 2609 respondents, of which 86% were laboratory professionals, 5% pathologists, and 2% trainees. We used a cross-sectional survey design for both surveys.

In terms of ethnicity, 75% identified as White/Caucasian, 5% as Black or African American, 9% as Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 % as Latinx, 0.6 % as Native American, 1% as West Asian, and 3.4% as other.

Limitations of this phase include a short survey deployment period, a low number of pathologist and trainee participants, and a lack of a diverse group of participants. There is also the potential for participant self-selection bias.

To mitigate these limitations, Phase 2 had a longer deployment period of one month and participants from a more diverse audience were targeted, including pathologists, trainees, and participants who do not identify as White or Caucasian. This phase also enlisted help from eight partner specialty organizations in the field of laboratory medicine to increase the reach of the survey. Finally, 31 additional questions were added to the initial survey to get more detailed information on the impact of DEI, the pandemic, burnout, and wellness. Repeat participants were prompted to only answer the additional questions. This time, there were 3,544 participants, of which 10.41% were repeat participants from our August survey. Of the 3,175 new participants, 82% were laboratory professionals, 7% were pathologists, and 2% were trainees.

In terms of ethnicity, 77% identified as White/Caucasian, 5% as Black or African American, 1% as African, 8% as Asian or Pacific Islander, 5% as Latinx, 1% as Native American, 1% as Middle Eastern/West Asian, and 3% as other.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Phase 1 Findings:

The initial phase of the study found that current burnout rates in the field of pathology and laboratory medicine were especially high. 52.5% of laboratory professionals, 46% of pathologists, and 27.10% of trainees indicated that they are experiencing burnout in the present and in the past. Additionally, 23.8% of laboratory professionals, 13.5% of pathologists, and 6.3% of trainees indicated that they are experiencing burnout in the present but not in the past.

We asked those who indicated that they were currently experiencing burnout if the COVID-19 pandemic caused or worsened their burnout. The pandemic caused burnout in 27% of laboratory professionals and 10% of pathologists and worsened the burnout of 51% of laboratory professionals and 30% of pathologists.

Of the factors contributing to participants’ burnout, laboratory professionals most frequently indicated the following factors: increased workload (60.4%), COVID-19 pandemic (54.6%), poor management culture (50.1%), work-related stressors (44.1%), and toxic work environment (31.4%). Pathologists indicated works related stressors (40.9%), increased workload (40.2%), poor management culture (37.8%), poor work-life balance (37%), and a toxic work environment.

Despite the high number of participants who identified as White/Caucasian (75%), 16.5% of pathologists and 7% of laboratory professionals stated that discrimination, sexism, racism, and microaggressions were contributing factors to their burnout. Additionally, 5.5% of pathologists and 7.8% of laboratory professionals mentioned grief and/or trauma as causes.

Phase 2 Findings:

The second phase of the study found that current burnout rates remained similar to the results of the first phase, with one significant difference. Present and past burnout rates among trainees increased from 27.10% to 44%. Additionally, 50% of laboratory professionals and 44% of pathologists indicated that they are experiencing burnout in the present and in the past. Additionally, 26% of laboratory professionals, 15% of pathologists, and 5% of trainees indicated that they are experiencing burnout in the present but not in the past.

The main contributing factors of burnout in phase two were the COVID-19 pandemic (66%), increased workload (64%), poor management culture (50%), work-related stressors (50%), and poor compensation (46%). In terms of DEI factors, 9% of all participants indicated that grief/trauma contributed to their burnout and 6.8% of participants mentioned discrimination, racism, sexism, and microaggressions.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Pathology and laboratory medicine play a crucial role in the nation’s health care system and the well-being of patients. The more data are available about how burnout impacts laboratory medicine, the more targeted and laboratory-specific solutions can be created. Burnout is a preventable, organizational phenomenon; this study offers solutions and recommendations to mitigate burnout in the field of laboratory medicine

The study identified differences in burnout rates between types of medical laboratory professionals, as well as between different demographics such as ethnicity. Results showed that organizational culture is a cause and a potential remedy to overcome burnout in the laboratory. The more open, inclusive, and well-staffed organizations are, the less likely medical professionals are to experience burnout.

Burnout: An Example of an Inter-relationship Between Health and Learning

Authors: Juliamaria Coromac-Medrano, BS, Nathaniel Williams, BA, Michael V. Williams, PhD, and Betsy White Williams, PhD, MPH

Institution: Professional Renewal Center®/Wales Behavioral Assessment

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Injury

Medical professionals are met with immense pressure and responsibility being at the front line of patient care. They also face ongoing stressors due to the continuous exploration for medical knowledge within the field of medicine, increasing administrative burdens, increasing patient demand, and a disproportionate low number of available physicians to treat patients (Williams et al., 2018).

With these external stressors in mind, a study conducted by Stewart and Arora (2019) found that nearly 50% of physicians report symptoms of clinical burnout, with the highest rates of burnout reported amongst family medicine, general internal medicine, and the emergency medicine specialties. Burnout has been associated with medical errors (Stewart and Arora, 2019), failure to maintain the expectations of professionalism in medicine and can be associated with poorer performance on neuropsychological tests (Williams et al., 2018).

We hypothesized that physicians who report high rates of burnout would perform more poorly on memory subtests of the California Verbal Learning Test 2nd Edition (CVLT-II) compared to physicians without high rates of burnout. Furthermore, we explored which of the three dimensions of the MBI (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment) correlated most strongly with impairments in memory scores.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

This study was reviewed and determined exempt by the WCG IRB. Data from a total of 280 clients were obtained from the Professional Renewal Center’s (PRC®) data sets containing information about clients from the time interval 2015-2019. All clients in the data set are physicians.

Subjects: This sample included 249 males and 31 females. The average age of the sample was 51.11 years.

Measure: Memory performances were measured with the California Verbal Learning Test, a test that requires the participant to learn and recall lists of words presented over several trials. Four of the memory subtests, short and long delayed cued and free recall, were analyzed. The free recall condition requires the participant to list the words they remember while in the cued recall condition the psychometrist provides a categorically-related prompt (cued recall).

We evaluated burnout using the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). The MBI-HSS captures three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment self-report. Emotional exhaustion is described as feeling emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work, depersonalization is the unfeeling and impersonal responses towards patients under the physician’s care, and reduced personal accomplishment is described as feelings of competence and successful achievement in one’s work with people (Maslach et al., 1997).

There are nine questions in the emotional exhaustion dimension, five in the depersonalization dimension, and eight in the reduced personal accomplishment dimension (Maslach et al., 1997). It is based on a six-point rating scale: Depersonalization (Low (0-6), Moderate (7-12), High (>27)), Emotional Exhaustion (Low (0-16), Moderate (17-26), High (>27)), Personal Accomplishment (Low (39)) (Dyrbye et al., 2009 & Lim et al., 2019).

Data Analysis: With this data set, a step-down regression model was utilized. Each dimension of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) was regressed on each recall section of the CVLT-II. The following parameters were regressed onto each CVLT subtest’s: MBI Emotional Exhaustion, MBI Personal Accomplishment, MBI Depersonalization, and the interactions between all three dimensions. The scores for each dimension were determined by the questions that fell under each category in the triad model

The results of the regression indicated that emotional exhaustion and to a lesser extent, depersonalization were the most active predictors of memory performance. The regression of emotional exhaustion onto the four memory subtests displayed significant results. Depersonalization was only significant for short delay free recall. Cued recall memory was the most sensitive of memory types. Free recall was found to be associated with the poorest performance with higher levels of emotional exhaustion. This means that clients who reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion had significant difficulty remembering the list of words without a prompt cue.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Burnout has been linked to changes that undermine physicians’ connections with patients and their colleagues, a decreased sense of motivation, interference with work-life integration (Amsten and Shanefelt, 2021). The uncontrollable stress in a physician’s environment that leads them to reporting burnout may impair the functioning of the prefrontal cortex (Amsten and Shanefelt, 2021 secondary to uncontrolled stress which can contribute to high levels of norepinephrine and dopamine impairing prefrontal cortex cognitive functions such as working memory.

From a cognitive perspective, cognitive load theory may provide insight into how burnout affects physician’s memory. This theory states task completion relies on an interplay between sensory inputs, “long-term memory acting as a repository of acquired knowledge and skills, with working memory as the intermediate stage, attributing meaning to sensory information,” and transferring the new information into long term memory (Iskander, 2018). Cognitive load directly refers to the amount of working memory that is devoted to synthesizing novel information and expanding current mental models to absorb new information (Harry et al., 2021).

Physicians are responsible for engaging in lifelong learning and maintaining their currency to achieve the best patient care. It is important to consider the potential implications of physician burnout on their ability to acquire new information and in turn the implication of that for CME/CPD.

Key Learning for CME/CPD Practice

Burnout is associated with aspects of learning and memory.

Learning requires working and active memory recall and retrieval. Clearly remembering new information is important to a physician’s remediation. There is evidence that assessing burnout-linked memory issues has implications for the pedagogical approach to remediating physicians.

Less effortful strategies such as cued recall and recognition may be a better measure of retention in physicians suffering from burnout.

References:

Amsten, F.T. & Shanafelt, T. (2021). Physician Distress and Burnout: The Neurobiological Perspective. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 96(3), 763+ https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A657476740/AONE?u=ksstate_ukans&sid=summon&xid= 9b70f63e

Dyrbye, West, C.P., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2009). Defining Burnout as a Dichotomous Variable. Journal of General Internal Medicine: JGIM, 24(3), 440-440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0876-6

Harry, E., Sinsky, C., Dyrbye, L. N., Makowski, M. S., Trockel, M., Carlasare, L. E., West, C. P., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2021). Physician Task Load and the Risk of Burnout Among US Physicians in a National Survey. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 47(2), 76-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.09.011

Iskander, M. (2019). Burnout, Cognitive Overload, and Metacognition in Medicine. Med.Sci.Educ. 29, 325-328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-006545

Lim, Ong, J., Ong, S., Hao, Y., Abdullah, H. R., Koh, D. L., & Mok, U. S. M. (2019). The Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory Can Overestimate Burnout: A Study of Anesthesiology Residents. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010061

Maslach, C., Leiter, M., & Jackson, S. E. (1997). The Maslach Burnout Inventory. The Scarecrow Press.

Stewart, N. H. & Arora, V. M. (2019) The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disorders on Physician Burnout. Chest, 156(5), 1022-1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.07.008

Williams, B., Flanders, P., Welindt, D., & Williams M. V. (2018). Importance of neuropsychological screening in physicans referred for performance conerns. PLoS ONE, 13(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207874

Developing a Mentorship Culture: Perspectives of Departmental Leadership on a Faculty Mentorship Program - A Qualitative Study

Authors: Michael Ren, BSc, Chloe Chan, Simrit Rana, Dorothy Choi, BSc, Umberin Najeeb, MD, Mireille Norris, MD, Simron Singh, MD, Karen EA Burns, MD, Sharon Straus, MD, Gillian Hawker, MD, Catherine Yu, MD

Institution: University of Toronto

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

Physician burnout is rising, and the issue is particularly complex among physicians in academic medicine. These physicians have multiple and often competing responsibilities because in addition to providing patient care, they are also involved in research and medical education (1). A potential strategy to mitigate this burnout is through faculty mentorship. There are many benefits associated with faculty mentorship including increased self-efficiency, greater career satisfaction, and higher faculty retention (2). The Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of medicine has created faculty mentorship program, however a process evaluation and an assessment on faculty mentorship needs is still lacking. Thus, we sought to understand the strengths and limitations of the department’s faculty mentorship program and identify opportunities for enhancement from the perspective of departmental leadership.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

Departmental Divisional Directors (of divisions with more than 10 faculty members), Vice Chairs, and two divisional mentorship facilitators were interviewed using a semi-structured guide exploring barriers and facilitators to mentorship, and current mentoring processes. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using qualitative descriptive approach.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Three emerging themes were identified: 1) Establishing a culture that encourages and values mentorship is paramount, and it necessitates a multilevel approach, 2) Mentorship barriers exist at various levels within an academic institution and 3) A tension exists between standardization vs individualization of mentorship processes.

There are various implications from these findings. In order to begin cultivating a mentorship culture, support and engagement is needed from all individuals within an academic institution. It involves faculty members understanding the value of mentorship as well as the academic institution recognizing its value and taking tangible steps to acknowledge and reward effective mentorship. Furthermore, when the department creates and implements mentorship processes, they need to be clear and flexible to address divisional and individual faculty nuances.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

This study highlights the challenges of addressing the diverse mentorship needs of physicians in academic medicine. It also outlines strategies to promote a culture of mentorship, with an emphasis on ensuring that individuals within an academic institution value and are engaged in mentorship activities, and that actionable steps are taken to recognize as well as maintain these values.

Relationship among Professionalism Concerns, Capacity, and Duration of Remediation

Authors: Hailey Amro, BA; Nathaniel Williams, BA; Michael Williams, PhD; Betsy W. Williams, PhD, MPH, FSACME

Institution: Professional Renewal Center® and Wales Behavioral Assessment

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

Physician performance failures are not rare but pose substantial threats to patient welfare and safety and can be usefully thought of as symptoms of underlying disorders and/or other contributory factors (Leape & Fromson, 2006). Past research has suggested that remediation can be an effective way to address physicians with problematic behaviors (Moskowitz, 2010).

The Environmentally Valid Learning Approach offers a framework within which to approach the remediation of physicians. The framework suggests that remediation of problematic behavior is dependent on multiple individual factors and considers other contributory factors, areas of knowledge/skills deficits, best approaches to addressing deficiencies, and elements that need to be in place to foster implementation and maintenance of gains. Capacity is one of the elements of the framework. Capacity is characterized by biopsychosocial factors and includes undiagnosed medical conditions, psychiatric conditions, and various social issues. In this study we focus specifically on capacity measures and how they relate to remediation length.

Approaches/Research Methods/Educational Design

Subjects: Data collected were from 103 physicians referred for remediation to a center in the Midwest. Part of the remediation process involves the collection of data that are used to inform the remediation approach. The physicians were independently identified as performing below expectations in the ABMS core competency area of professionalism prior to their arrival at the center. Specific behaviors of concern included difficulty establishing and maintaining appropriate boundaries with patients or staff, difficulty establishing appropriate boundaries around prescribing, behaviors that was disruptive to the functioning of the system, compliance issues, and health and well-being concerns (for example burnout).

Data Collection

Several self-report surveys were used to provide data that provided information about biopsychosocial functioning. Specific measures included the Ten-Item Personality inventory (TIPI) was used to collect data on personality factors, the DSM-V Anxiety Scale was used to determine the presence of anxiety, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was used to assess for burnout, the DSM-V Anger Scale was used to screen for anger while the DSM-V Sleep Scale was used to determine the quality of sleep received by our participants. Reported age was used to determine career point. The change questionnaire version 1.2 provided data on the participant’s understanding of the need to change. Length of remediation was operationalized as the participant’s dates of attendance in the program.

Analysis

This study was deemed to be exempt by WCG IRB.

Results

Physicians ranged in age from 23-69. Median age of the group was 49.06 years. Diagnostic = 56 and Procedural = 47.

A multivariate linear regression was used to analyze our data. The seven variables (personality, anxiety, burnout, anger, sleep, age, and belief in a need to change) together were correlated to the length of remediation. It was found that those seven variables together accounted for nearly half of the variance (R2 value of 0.48). Those results were found to be significant.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Results are consistent with the EVLA framework and highlight the importance of utilizing a multifactorial approach to behavioral change. Consistent with the broader literature and our earlier work, current results support the importance of biopsychosocial factors; for physicians to effectively learn and benefit from the content of the education within remediation, individual physician factors such as mood, burnout and physiological aspects need to be considered and addressed. Thus, while the acquisition of new knowledge and skills is an important part of a remediation process, knowledge and skills acquisition alone are not necessarily sufficient to fully remediate a physician with performance issues. This view is consistent of that of Durning (2011) and colleagues in their work with trainees. They discussed the importance of identifying and understanding the proximal causes of trainee underachievement, as without doing so it is difficult to pinpoint the most effective ways to assist trainees in improving their performance.

Key Learning for CME/CPD Practice

In relation to continuing medical education, our study suggests that success in a remedial learning application would be most effective if it contains a learner centric and multifactorial pedagogical approach to remediation as multiple factors are relevant to success and efficiency of the remediation process. Recognizing the potential contribution of biopsychosocial factors is important as remediation is less effective if such factors are not being addressed.

References

Durning, S., Cleary, T., Sandars, J., Hemmer, P., Kokotailo, P., & Artino, A. (2011). Perspective: Viewing "strugglers" through a different lens: How a self-regulated learning perspective can help medical educators with assessment and remediation. Academic Medicine, 86(4), 488-495.

Leape, L. L. & Fromson, J. A. (2006). Problem doctors: is there a system level solution? Annals Internal Medicine, 144(2), 107-115.

Moskowitz, P. S. (2010). RE: “Beyond substance abuse: Stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior”. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 7(4), 313-314.

Williams, B. W. & Williams, M. V. (2020). Understanding and remediating lapses in professionalism: Lessons from the island of last resort. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 109(2), 217-324.

Back To TopBuilding Capacity and Effective Teams

Adapting the Deteriorating Patient Simulation Method: Notes on the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Virtual Mental Health Simulation

Authors: Sanjeev Sockalingam, MD, MHPE, Noah Brierley, BA, Amanda Gambin, PhD, Thiyake Rajaratnam, MSc, Anne Kirvan, MSW, Michael Mak, MD, Chantalle Clarkin, PhD, Stephanie Sliekers, MEd, Fabienne Hargreaves, MA, Sophie Soklaridis, PhD, Allison Crawford, MD, PhD

Institutions: The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto

Purpose

Continuing professional development (CPD) programs in mental health are critical to building primary care teams’ capacity in mental health care. However, healthcare professionals often report barriers such as access to CPD and cost which limit uptake. Deteriorating Patient Simulation (DPS) is a team-based simulation activity that aims to mimic real-life medical situations that deteriorate over time. It involves an instructor acting out a patient scenario that deteriorates as the simulation progresses, and requires the learners to determine the appropriate steps to stabilize the patient. Throughout the process, the instructor facilitates the deterioration while simultaneously offering content knowledge. DPS was originally developed to support medical trainees in emergency medicine; the overall goal of this simulation activity is to promote learning by eliciting evidence based decision-making in a realistic scenario. DPS has not been used in a virtual setting or within a mental health context; as such, this study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a virtual mental health DPS educational activity with primary care teams.

Approach

The study was conducted in two phases: Phase 1 focused on the development of patient scenarios and a competency checklist as well as the feasibility and acceptability of delivering the simulation virtually. Phase 2 sought to refine the checklist and evaluate inter-rater reliability. During both phases, post-DPS focus groups were conducted to understand participants’ perceptions of the activity.

Two patient scenarios were developed using an interprofessional collaborative approach; evidence-based best practice guidelines were used to develop scenarios focused on a major depressive episode and suicide risk assessment. Each scenario had a unique algorithm for deterioration based on the teams’ decision-making. The competency checklist was developed by content expert review including the primary investigators and mapped to case scenario goals and objectives.

Participants were previous participants of ECHO Ontario Mental Health at CAMH and University of Toronto. Generally, participant groups consisted of at least 1 prescribing professional (i.e. MD, NP) and 2 other healthcare professionals. DPS sessions were delivered via Zoom and were typically 2 hours in duration: the 60-minute DPS activity was followed by a facilitator-led debrief (30 minute) and a focus group (30-minute). Participant performance was scored by a third party rater using the competency checklist developed by the team.

Evaluation

Seventeen (17) healthcare providers (3 MD, 3 NP, 5 SW, 2 RN, 2 other) participated across 6 DPS sessions. Moderate inter-rater reliability was established for the DPS checklist (66% agreement). Focus group data highlighted barriers and facilitators to the activity. Participants responded positively to the structure and facilitation of the activity, and emphasized the simulation-based feedback from the post-activity debrief as integral to their learning. The DPS activity was described as valuable and appropriate for skill building, and the team-based nature of the activity provided an important interprofessional lens to patient management. Participants noted time constraints, as well as the formation of “artificial teams” specifically for this activity as challenges.

Key learnings for CME/CPD Practice

This pilot study provides evidence to support the potential use of virtual DPS as an accessible, low barrier, CPD activity to increase provider competency in mental health clinical decision-making. Further development of this activity could include use as an educational assessment tool, and to increase mental healthcare capacity in primary care teams.

Beyond Grand! Grafting a Structured Reflective Tool to Hospital Rounds

Authors: Sam J. Daniel, MD, MSc, FRCSC, Jane Tipping, MADEd, MCC

Institution: McGill University, Federation of Medical Specialists of Quebec, University of Toronto

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

In many institutions, grand rounds are a weekly educational activity and a time-honored tradition. Unfortunately, hospital-based grand rounds lack uniformity in value for the learners. Our goal was to make these group learning activities more conducive to a change in the clinicians’ performance by increasing critical thinking and enhancing engagement in rounds using a simple, structured, reflection tool.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

A reflection tool was systematically grafted after each grand rounds. The tool was based on Borton’s model of reflection (description, analysis, synthesis). It guided participants to reflect on their learning, by identifying a concrete enhancement in their practice, reflecting on barriers and facilitators, and stating a strategy and a timeline for implementation. A focus group was surveyed as to their experience with this tool through a structured interview.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

To date over 300 reflection tools have been collected. 80% of the participants felt that the grand rounds were relevant to their practice.

The most common barriers to implementing changes were time, followed by human resources and equipment issues.

Interviewees listed 4 key aspects of learning upon which the reflective survey touched:

- Encouraging critical thinking,

- Encouraging reflection,

- Engaging learners, and moving beyond passive learning, and

- Increasing the likelihood of application to practice.

Adding a reflection tool to grand rounds was successfully implemented. Participants valued the survey in reinforcing key concepts and integrating these concepts into practice. This tool continues to be popular 2 years after its deployment and is extending to other centres.

Facilitators included making the tool available immediately after rounds, and having champions participate and advocate for the tool.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Adding a reflection tool, after grand rounds can transform CPD for group learning activities into active learning and allows participants to immediately initiate a Deming cycle with the identification of a change, and an action plan to implement it.

Holding Braver Conversations: Interpersonal Conflict Simulations

Authors: Trung Do, RN, BN, Kamini Kalia, RN, MScN, CPMHN(C), Stephanie Sliekers, Med, Tucker Gordon

Institution: University of Toronto, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Purpose/problem statement

During the COVID-19 pandemic, retention of clinicians has been priority, which has placed additional pressure on healthcare teams to work effectively and cohesively together. Education for new hires about how to handle challenging conversations with their peers can reduce experiences of interpersonal conflict, improve team collaboration, and resiliency.

Methods/Approach(es)

Utilizing the ERASE Framework, Cognitive Rehearsal Training, and Simulation teaching methods, an educational module for interprofessional teams was developed for newly hired clinicians. The training was designed to facilitate application of interpersonal conflict resolution skills with their colleagues utilizing role plays. A quality improvement framework was utilized using rapid review cycles to make quick and iterative improvements to education based on feedback.

Outcomes/Findings

Participants provided structured feedback in the form of in-person and post-session evaluations. Participants reported feeling supported by the organization as it was perceived by learners as an organizational priority. Participants also reported that the content was relevant and that they received guidance on how to respond to difficult situations as the scenarios were seen to be likely to arise in the workplace.

Discussion

A multi-pronged strategy is required to address issues of interpersonal conflict in interprofessional teams. These sessions highlight the need to also create structures and supports for faculty who deliver the education.

Barriers/facilitations

There are opportunities to strengthen the delivery method utilizing different types of simulation technology.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Interpersonal conflict impacts all clinical roles and healthcare leaders have an opportunity through the use of simulation to offer options that that cultivate psychologically safe environments and confidence to have braver conversations.

How to Collaborate Successfully in Online Educational Programs for Latin America

Authors: Alvaro Margolis, MD, MS, Jann Balmer, PhD, RN, Steven Kawczak, PhD

Institution: EviMed (AM), University of Virginia (JB), Cleveland Clinic (SK)

Purpose/Problem

International collaborative programs in CME/CPD are of interest for many North American institutions. However, they pose different types of challenges, in terms of educational design, accreditation, convening or evaluation, but also in the need to address cultural and language barriers in order to be successful.

Latin America is a large and heterogeneous middle-income region, with one million physicians. One third of the region, by several counts, is Brazil, where Portuguese is spoken, while the rest of the countries speak Spanish. This dynamic creates an opportunity for online activities to be tailored to learner characteristics regionally and delivered in the two main native languages of the region.

The University of Virginia Office of Continuing Medical Education has been involved in web-based and innovative continuing education for physicians, nurses and healthcare professionals for over thirty years. The Center for Continuing Education at Cleveland Clinic is dedicated to providing a wide array of quality continuing medical education opportunities to medical professionals throughout the world. EviMed is a company that provides multilingual online programs for healthcare professionals across the Americas.

The COVID-19 Pandemic accelerated the collaboration between each of the two North American organizations and EviMed, and with other Latin American academic partners. The authors describe their experience in international collaborative educational programs for Latin America, in order to help other parties reflect on their own challenges and path towards the implementation of international programs with developing countries and regions.

Methods/Approaches

One program was implemented for Latin America with each of the North American institutions: 1) A nephrology course about kidney transplant in 2020 with the University of Virginia (which was relaunched in English for North America in 2021); and 2) an intensive care course about end-of-life care in the ICU in 2021, with the Cleveland Clinic, which was aimed at North America and Latin America at the same time (in English, Spanish and Portuguese).

Each program averaged 25-30 hours of study over two months, and was designed as a mostly asynchronous educational intervention with social learning for massive audiences (1). Approximately 20 experts from Latin America and North America participated in each of the courses in different roles, such as coordinators, speakers, content developers and native-speaking moderators. Courses were developed in partnership with each of the two North American institutions and different academic organizations of the Latin American region, including the Brazilian Society of Intensive Care Medicine (AMIB), the Argentinean Society of Critical Care Medicine (SATI) and the Brazilian Society of Nephrology (SBN).

Each online course included study materials, in the form of texts and videos, as well as different types of activities, including discussion forums on clinical cases and clinical simulations. Simulations allowed the participant to navigate through a clinical scenario with several possible paths, where maybe more than one is correct, as in real life. Feedback is given in each step of the process. The discussion forums are virtual spaces that foster interaction with other course participants and with Faculty in their native languages (Spanish and Portuguese) The asynchronous nature of these spaces allowed the course attendees to participate whenever they could. Finally, live interactive Webinars were also part of these courses, as launching events and as synchronous conversations with the experts.

Outcomes

In the first program, (kidney transplant, 2020), there were 824 participants from 22 countries: Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina were the top five participating countries. The second program (end-of-life care in the ICU, 2021) had 490 participants from Latin America, North America and Europe: 219 participants in the Spanish-speaking campus, 234 in the Portuguese-speaking campus and 37 in the English-speaking campus.

Regarding engagement throughout the activity, it was high along the two months in both courses despite the massive audiences. As an example, the approval requirement at the 8th week of the kidney transplant course was 60% (in this case, it was to complete a commitment to change statement). This is probably related to the social interaction among participants and with Faculty, based on social learning analytics (1).

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

These programs were targeted at Interprofessional audiences with a focus on teams, and had several distinctive instructional design elements, such as being longitudinal and asynchronous/self-paced, with community and social learning, addressing massive audiences of healthcare professionals, and multilingual with a wide geographic reach. The above required collaboration to create and deliver education across languages, countries, organizations and cultures. On top of it, the pandemic created its own set of challenges and uncertainties, which necessitated flexibility and swift response in order to adapt to foreseen and unforeseen challenges.

Finally, since the educational format was new for several of the Faculty and attendees, there was a clear need for Faculty development regarding tutoring in virtual spaces, and setting up learner expectations, which also included active participation in the asynchronous conversations in order to take the most of the learning experience. 1. Margolis A, López-Arredondo A, García S et al. Social learning in large online audiences of health professionals: Improving dialogue with automated tools [version 2]. MedEdPublish 2019, 8:55 (https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000055.2)

Monitoring and Evaluating AI: Challenges and Practical Implications

Authors: Carlye Armstrong, Alexis LaCount, Alison Loughlin, Christopher Treml

Institution: American College of Radiology

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

The use of technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in medicine is currently a topic of great interest, especially with regard to diagnostic or predictive analysis of medical images. Yet AI is frequently termed a “black box” because health care professionals often have limited understanding of how it was developed and what issues may arise once AI is put into place. Health care professionals need to be empowered to use and create AI tools to meet patient needs. However, those most qualified to teach health care professionals about AI are often involved in developing AI or working with AI vendors. By integrating AI technology content into continuing education programs and recognizing the common overlap in medical professionals developing commercially available algorithms and teaching other professionals how algorithms are developed and trained CPD professionals can aim to address population health issues in the content they plan, implement and evaluate.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

Learners gained an understanding of AI terms and concepts and learned how to establish processes for vetting AI technology content into their own continuing education programs, with the ultimate aim to positively impact patient health. Learners had the opportunity to analyze case scenarios where AI may help improve care, identifying gaps/needs and learning objectives to plan a continuing education program.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

The American College of Radiology (ACR) is uniquely positioned to plan, implement and evaluate continuing education content centered on the use of AI by clinicians. The ACR’s Data Science Institute was developed to facilitate the development and implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) applications that will help radiology professionals provide improved medical care. ACR’s AI-LAB™ provides learners the ability to develop their own AI model for a specific AI use case. Learners define the problem, prepare the data, configure their own AI model and train and test the model for potential use in practice. Further, ACR hosts accredited continuing education geared at monitoring and evaluating AI in practice.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Key learning for CME/CPD practice include: knowledge of basic AI terms, concepts and development; identification of challenges to use of AI in clinical practice; and steps to begin collaborating; and contributing to the development of AI-centered, accredited continuing education. A specific focus was placed on integrating AI technology content into continuing education programs to address population health quality gaps, with the ultimate aim to positively impact patient health based on the ACR’s experience with their continuing education program focused on AI.

Practice Assessment Tools for Medical Specialists—A Bridge to Quality Improvement

Authors: Martin Tremblay, PhD, Sam J. Daniel, MD

Institution: Federation of Medical Specialists of Quebec

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

Canada’s maintenance of certification (MOC) programs for physicians have evolved to emphasize assessment activities. Our organization has recognized the importance of providing more practice assessment opportunities for our 10,000 members to enhance their practice and help them comply with current regulations. We developed an innovative approach to structure practice-based assessments.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

Based on the Deming Cycle framework (Plan-Do-Study-Act), we developed a series of structured practice assessment documents allowing physicians to 1) determine their needs, 2) establish quality indicators, 3) analyze their practice, 4) get feedback, and 5) develop an improvement plan.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Twenty-one practice assessment tools have been developed. They have been downloaded over 2,500 times by physicians from all 35 of our affiliated medical associations. Participants indicated that these were relevant to their practice (98%), helped them identify opportunities for improvement (97%), and prompted them to change aspect(s) of their practice (96%). These practice assessment tools are aimed at helping physicians identify knowledge or performance gaps that can be addressed with practice adjustments or further educational activities. Covering all seven CanMEDS competencies, they are intended to enable physicians claim MOC credits following various assessment activities, and unlike other assessment activities, they can be reused several times during the same MOC cycle. A collaboration with leaders from our affiliated medical associations and an efficient dissemination strategy were essential for the success of this ongoing initiative.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Based on a quality improvement framework, we developed tools to facilitate practice assessment and identify improvement opportunities following formal and informal activities. A better integration of quality improvement principles within the discipline of CPD could improve both educational and practice-based issues.

Proactive Partnership and Project Management: A Successful Model to integrate CME into Daily Clinical Practice

Authors: Sandhya Venugopal, MD, MS-HPEd, Erik G. Laurin, MD, Shelley A. Palumbo, MS, Glee Van Loon, RD

Institution: University of California, Davis Health

Problem Statement

Education embedded in clinical practice for positive outcomes is the epitome of CME/CPD. Realizing this in a large academic medical organization, however, is not easily achieved. To effect such change, the University of California, Davis, Health Office of Continuing Medical Education (OCME) determined a multi-faceted approach built on early partnership and project management to develop quality improvement initiatives, the first of which focused on inpatient glycemic control.

Methods/Approaches

Although OCME has long been a part of quality improvement coursework, OCME needs to be involved at the ground level, ideally when gaps and needs are first identified, to effectively incorporate educational materials into daily clinical practice. To achieve this step, numerous meetings were held with leaders involved in quality initiatives across the organization, including the Chief Quality Officer. These meetings highlighted the value OCME could offer if integrated early in the process and outlined the logistics of providing educational content to address the needs.

OCME’s philosophy is that partnership is based on mutual respect and when each team member’s talents are valued regardless of their role. Everyone recognizes the value of the subject matter experts (SMEs), but equally important is the OCME team’s expertise. By welcoming OCME to develop curriculum in partnership with the Quality Office and SMEs from the outset, everyone’s expertise can be leveraged, and roles are clearly defined from the start.

The most successful projects have been those in which OCME project manages all phases of curriculum design, development, delivery, and evaluation. Project management is not to be confused with event planning, historically associated with CME. The project manager focuses on the core elements of the curriculum, leads all phases of the course lifecycle, and ensures integration into clinical practice. The inclusion of practical tools for retention and sustainability and evaluation components to measure outcomes are critical.

Outcomes

The early partnership of OCME and the quality office demonstrated the effectiveness of this model with the formation of a new inpatient glycemic control curriculum. Two learning modules were created to educate learners on ways to improve care for patients with Type 1 and 2 Diabetes Mellitus and stress-induced hyperglycemia through use of clinical decision support tools and an electronic medical record (EMR) subcutaneous insulin order set. Course content included standards of care published by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the application of standards into practice. Pocket reference guides were also made available for use in practice.

As a result of this CME coursework, management guidelines were updated and practice changes at an institutional level were made as demonstrated by:

- Over 1650 learners have completed the glycemic coursework to date.

- 60% of providers are now using the new Adult Subcutaneous Order Set since the launch of the two CME courses.

- The courses were highlighted during the UC Davis Health Quality and Safety Committee meeting as a Vizient Scorecard presentation under the topic of safety for reducing surgical site infections.

- A trifold of the clinical decision support tools was created as a supplement to the coursework to guide physiologic insulin in accordance with ADA standards of care for inpatient diabetes/hyperglycemia.

- Updated insulin tables now reflect coursework and order set changes within the EMR.

- Updated wording of “Adult Protocol for Insulin Infusion”

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

Quality CME that permeates daily practice is possible, but several variables must be addressed to ensure success. The gaps and educational needs must be clear and have leadership support. Education must be harmonious with existing clinical processes for integration into practice. Evaluation measures identified from the beginning are critical to determine outcomes. Adjunct educational tools are beneficial for long-term sustainability. Lastly, having OCME employees with the skills to project manage these factors is essential.

The utilization of a CME project management model facilitates best practice and ensures curriculum is developed in a manner that includes multiple integrative elements. By applying this approach, it is possible to incorporate education into daily practice. While project management is not a new concept, it is not widely applied in CME/CPD. Given the clear benefits, this approach may be considered for initiatives requiring widespread change.

Developing a Patient Safety Culture Training Curriculum for Healthcare Professionals

Authors: Eulaine Ma, BSc, Wei Wei, BSc, Certina Ho, BScPhm, PhD

Institution: Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

The Patient Safety Reporting and Learning (PSRL) Committee of the Manitoba Institute for Patient Safety (which is now under Shared Health’s Quality and Learning service in Manitoba, Canada) was committed to develop a community-based incident reporting and learning system for multi-disciplinary healthcare professionals in Manitoba. The PSRL Committee was fully aware that building and nurturing safety culture among all health professions was a prerequisite for developing and maintaining an effective patient safety incident reporting and learning system. Lessons learned from other reporting and learning systems around the world reflected that low reporting and utilization rates of such programs were associated with poor safety culture. On the other hand, having a patient safety culture is a facilitator for incident reporting and learning.

Patient safety culture is defined as the shared organizational belief and behavioural pattern that focuses on maximizing patient safety and minimizing patient harm. It is a key component of enhancing patient safety, and therefore quality of care. As well, establishing and maintaining a patient safety culture is an indispensable prerequisite for an organization or a regulatory authority to implement any patient safety and quality improvement initiatives.

The purpose of our project was to identify existing patient safety culture education guiding documents, synthesize these materials, and develop a specific curriculum for training healthcare professionals on safety culture. Ultimately, this patient safety culture curriculum will not only support a multi-disciplinary provincial regulatory authority (e.g., in Manitoba, Canada) in advocating for patient safety culture and province-wide quality improvement initiatives, but also aid in establishing or improving safety culture in any organization.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

A formal literature search on MEDLINE® and EMBASE was performed for training materials specific to patient safety culture but did not return any results that the PSRL Committee and patient safety stakeholders could readily use or apply to meet their needs in Manitoba. Thus, we discovered that there is a paucity of ready-to-use and translatable patient safety culture training materials in the literature for regulatory or health professional bodies to apply across a multi-disciplinary healthcare setting.

We then performed a grey literature search to find relevant guiding documents from patient safety organizations, including those in the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, United States (US), Australia, New Zealand, and the World Health Organization (WHO), all of which have either similar health systems or established patient safety organizations or efforts. To identify websites of regulatory authorities and policy institutes responsible for patient safety, we used a simple Google search, then located relevant documents on these sites via targeted Google search. This involved using Google search queries related to patient safety that were restricted to a particular organization’s website.

To synthesize the patient safety culture curriculum, individual domains, competencies, or relevant themes from our identified patient safety education guiding documents were compared and overlapping competencies relevant to patient safety culture were extracted. Common patient safety culture topics were constructed into a curriculum using Bloom’s taxonomy and the Knowledge, Skills, Attitude learning outcome categories. (Figure 1 – link to Safety Culture Curriculum Syllabus for HCPs 18Feb2022.PDF)

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

Four patient safety education guiding documents were identified. These documents were National Patient Safety Syllabus 1.0 (National Health Service, 2020), The Safety Competencies (Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2020), Safer Together: A National Action Plan to Advance Patient Safety (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2020), and the Patient Safety Curriculum Guide (Multi-professional Edition) (WHO, 2011). The curriculum was synthesized with a total of five competencies and 21 learning objectives. The five competencies are organizational culture, just culture, safety improvement and evaluation, information sharing and transparency, and safety leadership. (Figure 1)

Organizational culture and just culture address barriers and facilitators to reporting safety incidents. Regarding organizational culture, including patient safety in an organization’s values or vision encourages engagement from staff and facilitates incident reporting. A just culture is about approaching errors from a system perspective rather than blaming and shaming individuals involved, which can remove a significant barrier for reporting. Both themes help set the tone for safety culture from a bottom-up perspective within a workplace or practice setting.

A top-down perspective is related to safety leadership. Safety leaders promote safety culture through leading by example and inspiring others to appreciate the value of patient safety culture. They also oversee and reinforce the organizational culture and just culture, our last two competencies, by facilitating the use of quality improvement and reporting tools. Safety leadership also has a bottom-up contribution, where safety leaders empower healthcare providers within a team to be safety leaders themselves, promoting safety culture and engaging colleagues to embrace and uphold organizational and just culture, the first two competencies.

Safety improvement and evaluation highlights the need to measure patient safety through enabling healthcare providers, patients, and families to report and share safety incidents. These incidents should also be appropriately evaluated and analyzed to determine root causes, contributing factors, and areas of improvement. Information sharing and transparency is a related, but separate competency that emphasizes the importance of closing the loop on reported incidents, which can be done through analysis and dissemination of shared learnings. Both themes can be addressed simultaneously with continuous quality improvement initiatives supported by an accessible, user-friendly, and well received/used patient safety incident reporting and learning system.

Key Learnings for CME/CPD Practice

The Safety Culture Curriculum for Health Care Professionals (Figure 1) serves as a step forward in creating ready-to-use and translatable patient safety culture training materials for healthcare providers. It can be used to develop educational or training modules specific to any levels within an organization, including teams, institutions, or jurisdictions. All five competencies should be addressed in a patient safety culture curriculum, which can be further guided by the learning objectives suggested within each competency domain (Figure 1).

The topic of patient safety culture, although often explored in undergraduate training for medical and healthcare professions, continue to be significant and relevant when one begins their clinical practice with direct patient care. Therefore, patient safety culture training is well suited for CME/CPD for healthcare practitioners. Potential next steps of the Safety Culture Curriculum for Health Care Professionals (Figure 1) include content creation, development, and delivery of materials, such as training courses, modules, workshops, or seminars, etc., which can be pilot tested virtually and/or locally at targeted sites or jurisdictions to obtain feedback and lessons learned. Specific learning objectives may also be adapted and integrated into existing “in-house” patient safety training programs at different institutions, to provide insights on how the curriculum may be operationalized in real-world healthcare settings. The cultural context of a practice setting has an impact on the practice of a healthcare provider or a team, and subsequently the quality and safety of patient care. The myriad of educational sessions organized by local CME/CPD programs offer great opportunities for CME/CPD providers to utilize or adapt the curriculum in an innovative and customized manner, as part of a concerted effort to build and promote patient safety culture in the workplace. The Safety Culture Curriculum for Health Care Professionals (Figure 1) may serve as a primer for further education and research in patient safety culture, as greater inclusion of human and system factors that affect patient care in CME/CPD programs is warranted.

Impact of Interprofessional vs Non-interprofessional Continuing Education Activities on Learning, Competence, and Performance Pertaining to Interprofessional Collaborative Practice

Authors: Marianna Shershneva, MD, PhD, Barbara Anderson, MS

Institution: Office of Continuing Professional Development, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Purpose/Problem Statement/Scope of Inquiry

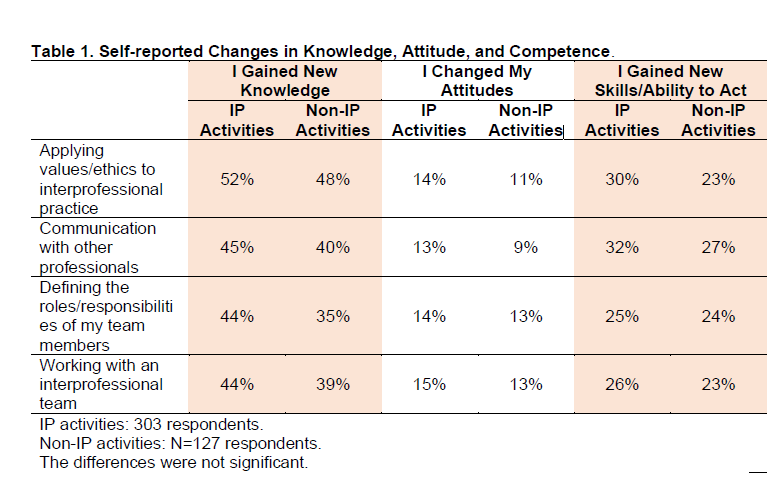

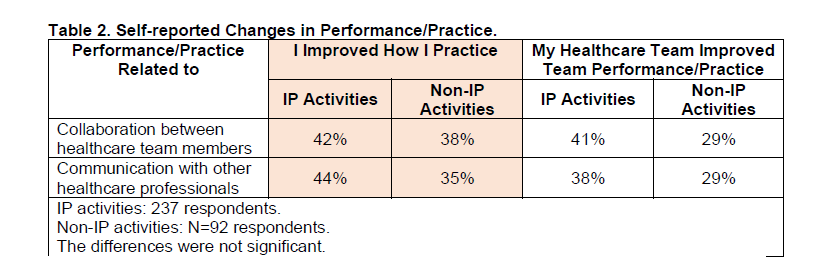

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Interprofessional Continuing Education Partnership (ICEP) conducts an annual survey of participants in the ICEP-accredited activities. Analysis of responses to open-ended questions about the educational impact from the 2016-2020 surveys documented that reported changes in competence and performance resulting from participation in interprofessional (IP) as well as non-interprofessional (non-IP) activities included statements consistent with collaborative practice. This observation and a transition from open-ended to multiple choice survey questions pertaining to the educational impact created an opportunity to examine outcomes from IP activities in comparison with non-IP activities. We used the results of the 2021 survey to answer two questions. Did non-IP activities have impact in areas consistent with IP, collaborative practice? Was this impact comparable to the impact of IP activities? Moore’s levels of evaluation and four domains of IP practice informed our inquiry.

Approach(es)/Research Method(s)/Educational Design

The survey included blocks of questions about live, enduring, and regularly scheduled series (RSS) activities. Respondents could select one activity they participated in (or none) from a list in each block, and then evaluate the selected activity by responding to the related questions. We analyzed responses to the following questions:

- Did participation in this activity impact your knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills/strategy/ability to act pertaining to your practice?

- Those who answered “yes”, were asked: How did you change your knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills/ability to act? Respondents could select all that applied; 4 of 12 listed categories pertained to IP practice.

- Did participation in this activity impact your and/or your healthcare team performance/practice?

- Those who responded “yes”, were asked: How did you and/or your healthcare team improve performance/practice? Respondents could select all that applied; 2 of 18 listed categories pertained to IP practice.

Responses pertaining to domains of IP practice were compared for IP activities vs non-IP activities using Fisher exact test with significance level P<0.05.

Evaluation/Outcomes/Discussion

A total of 602 education participants representing more than 20 professions responded to the survey. Distribution by profession is shown in Figure 1 below.